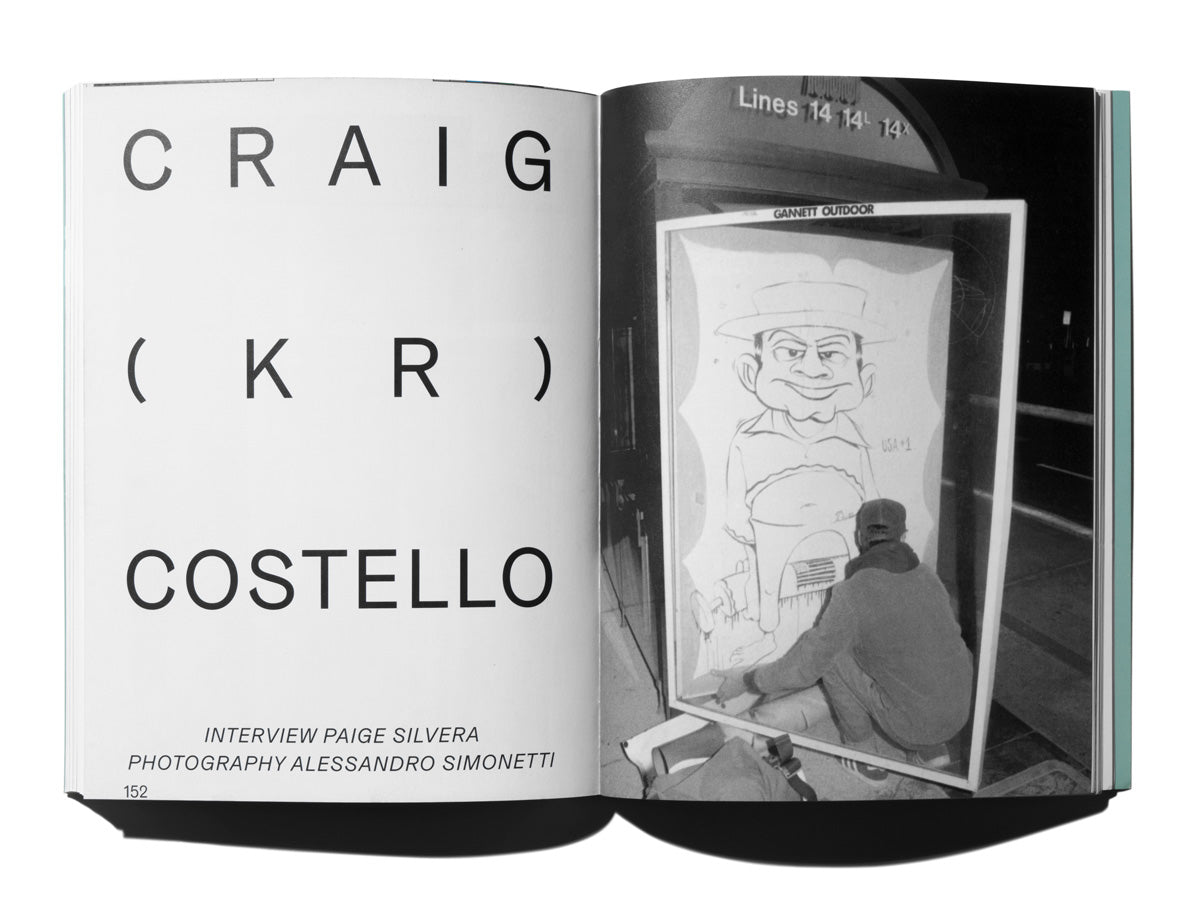

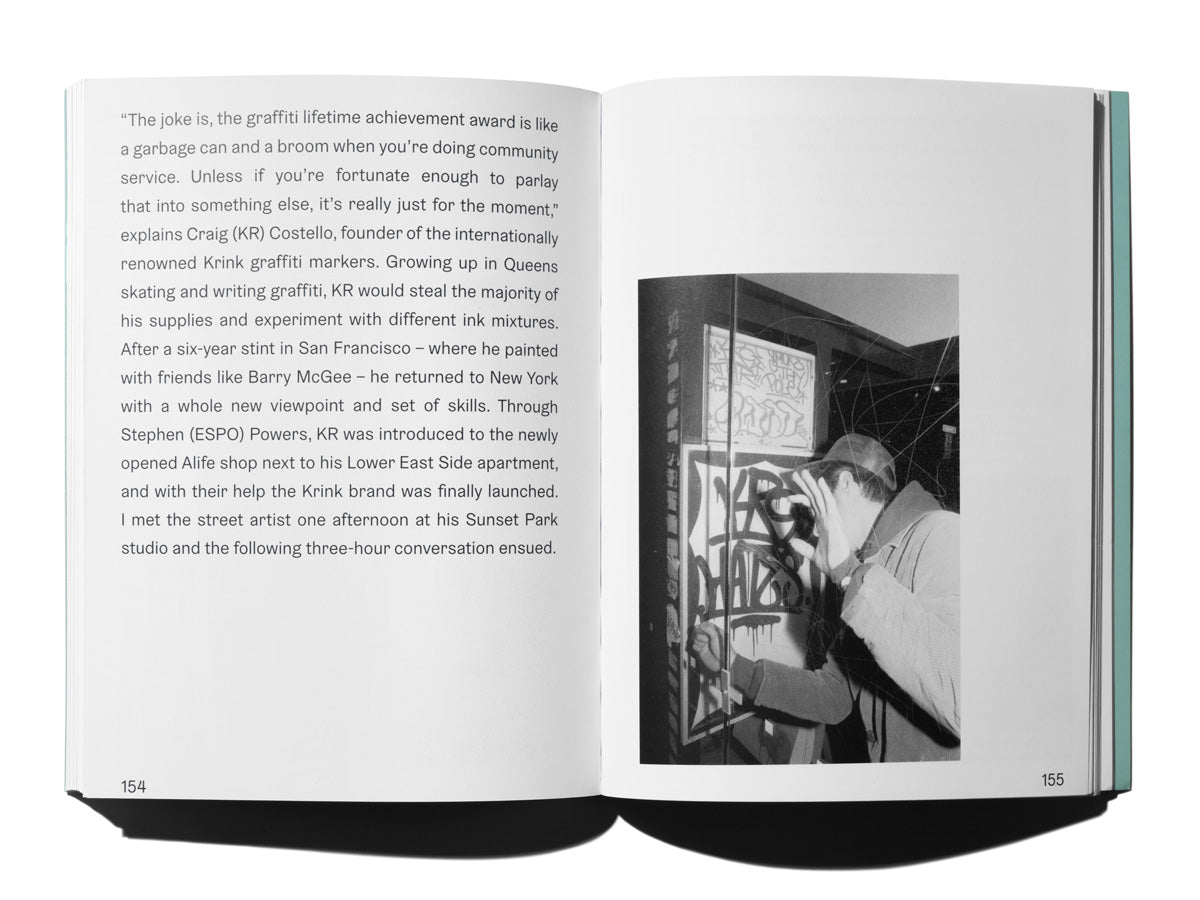

“The joke is, the graffiti lifetime achievement award is like a garbage can and a broom when you’re doing community service. Unless if you’re fortunate enough to parlay that into something else, it’s really just for the moment,” explains Craig (KR) Costello, founder of the internationally renowned Krink graffiti markers. Growing up in Queens skating and writing graffiti, KR would steal the majority of his supplies and experiment with different ink mixtures. After a six-year stint in San Francisco — where he painted with friends like Barry McGee — he returned to New York with a whole new viewpoint and set of skills. Through Stephen (ESPO) Powers, KR was introduced to the newly opened Alife shop next to his Lower East Side apartment, and with their help the Krink brand was finally launched. I met the street artist one afternoon at his Sunset Park studio and the following three-hour conversation ensued.

Paige Silveria: Let’s start from the beginning. Where in New York did you grow up?

Craig KR Costello: Forest Hills in Queens. I grew up in a neighborhood with houses and families and a lot of the people that grew up there, stayed there. You knew your neighbors. A lot of times in New York City you step out your door and it’s a lot of strangers. But I’ve always had a community. When I was a teenager we started going to the city. Back in the day, W4th was where you’d take the train to. As a kid we didn’t really have any money so it was skating around, drinking, doing some graffiti. We just hung out in the street. Today you’d be arrested or given tickets. It was a very different city back then.

What were your cultural influences as a kid?

There was hip-hop that was really still new. We’re talking like ’86. I was into punk and new wave and coming out of a base of like classical rock. I was into skating back then but it was mostly based in California. I’d look at Thrasher mag and see these drainage ditches and I didn’t even know what I was looking at — it was just in the desert somewhere. Versus street skating, which is what we had here. We used to go to JFK and skate. That was our spot all of the time.

Whoa, inside the terminal?

Yeah it was crazy. Today they wouldn’t let you do anything the way we used to do it. We used to skate at night — we’d bring beer and weed — we’d skate the international halls. They were smooth and you could do these slides. We’d go to TWA, which is now JetBlue, but they destroyed most of it. It used to have banks that we’d skate. No one ever messed with us. There was a lot of free-for-all. They’d tell us, “Hey kid, get out of here.” But there weren’t any arrests and nothing was locked down. Everything was really open. We also went to The Met as kids and hung out on the steps. You could go inside for a nickel. It was just there for you. MoMA had a great bookstore back then. Amazon just decimated all the bookstores. I grew up when there were a lot of small businesses. The cheese spot, meat spot, Italian deli and the bookstore.

What kind of student were you?

I was kind of a bad student. But I read on my own. Everything from Kurt Vonnegut, Woody Allen, Steve Martin, Camus, Kafka — those were weird books that I was into. I think they influenced me later.

How’d they influence you?

Hard to say exactly.

Where did you buy your skateboards back then?

Soho Skates was really the only place … there was another shop uptown maybe in the low 80s or high 70s. I bought all my boards at Soho Skates though. My first board had all the plastic shit on it. It was so funny. I had a Vision Street Ghost board. And when I started skating more and breaking shit, I got all hand-me-downs. There was only the occasional new deck. And you’d put it together yourself. Whereas your first deck came fully assembled. You got parts from your friends and tried new wheels. I grew up in this culture of DIY, taking things apart. You make your own ramps and look at your environment for places to go do what it is that you want to do.

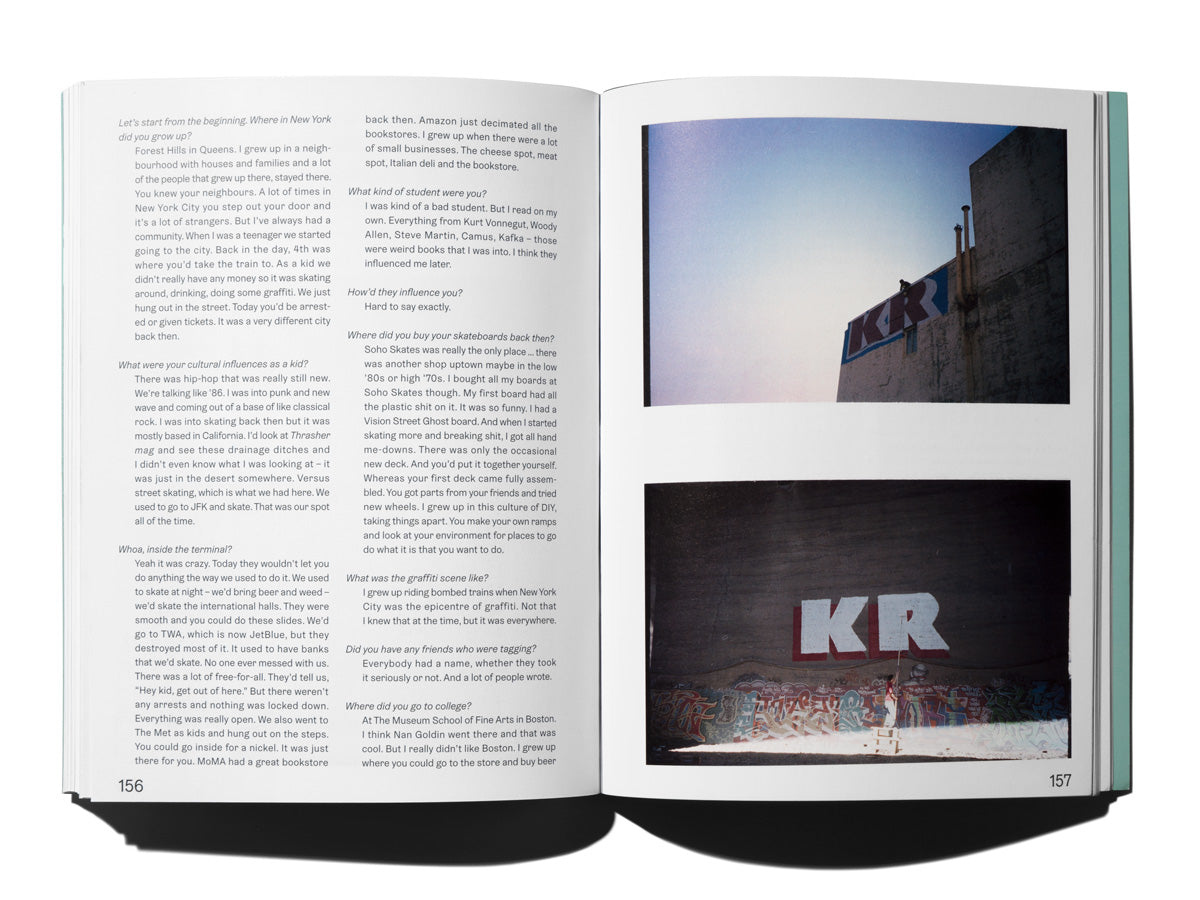

What was the graffiti scene like?

I grew up riding bombed trains when New York City was the epicenter of graffiti. Not that I knew that at the time, but it was everywhere.

Did you have any friends who were tagging?

Everybody had a name, whether they took it seriously or not. And a lot of people wrote.

Where did you go to college?

At The Museum School of Fine Arts in Boston. I think Nan Goldin went there and that was cool. But I really didn’t like Boston. I grew up where you could go to the store and buy beer and hang with your friends. It was freer. When I was 17 I was into the hardcore scene. We’d go to shows and things. But Boston was so locked down. You couldn’t buy beer. If you asked someone to go and buy you beer, they’d go into the store and tell the clerk on you. That blew our minds. We were denied things that we took for granted. I was also an alternative kid. And Boston was douchey. I didn’t grow up with the football team and what you see in the movies. And there there would be like these big jock dudes trying to pick fights with me. It was just a weird scene and I wasn’t into it. It wasn’t very diverse. So I dropped out of school and left.

Where’d you go?

I moved back to New York but I’d had this taste of freedom so it was hard to be back home. I had this opportunity to go to SF so I did. I worked at a one-hour photo store. You see a lot of things working at those spots. A lot of the photos were cyclical. You see that people take the same high school and birthday photos. And everyone is a bad photographer. It was just a bullshit job. After that I knew I didn’t want to deal in retail. That’s why we only sell our Krink products wholesale.

Where in San Francisco did you live?

In the Sunset. It was really close to the beach. We redid the whole house. It was crazy. We had Chinese landlords. The place was just poorly painted and they had linoleum tile on the walls. Being from here, moving out there was a really great experience. I had a garden. I watched broccoli grow.

What was the graffiti scene like there at the time?

It was all pre-Internet, so ideas didn’t travel as fast. The world’s gotten a lot smaller. Like now you can go to Berlin and the kids will be dressed exactly like kids in Bushwick. But back then it wasn’t like that yet. People didn’t travel as much. So I was coming from New York, a completely different gene pool and arriving with different ideas about how and where you did things. My writing methods and things were different. The term racking means stealing your supplies, and they were all way more accessible in Cali. In New York, it was more locked down. SF was really small so the scene was really small. There were really only pockets of graffiti, like in parking lots. They didn’t have as much as we did in New York. Of the graffiti writers there were only a few that stood out. Barry McGee was one of them. He seemed down to do shit. We met through a mutual friend. (For me, graffiti is partner driven; a two-man team is the best because you have an extra set of eyes. Three people can be too much and four is way too much.) And then I met other people and I got more involved in graffiti out there. And I stood out. What I was doing was completely different than anyone else.

How so?

I was not a very good graffiti writer. I wasn’t the prettiest. Graffiti was arrows and colors and I’m not that guy. I’m more like ubiquitous: a lot of throw ups and splats and black and white and simple. It was very New York at the time. We had two kinds of spray paint, really. There’s Krylon and then there’s Rust-Oleum. Krylon sprays a finer line; it’s not as robust. Rust-Oleum is not as fine but it can cover brick and all kinds of things. Krylon, it’s got a great logo; that’s the known brand. It’s also colorful. So if you do your piece and you’ve got your arrows, you’re going to be using Krylon. But if you went to paint a brick wall with Krylon colors, it’d just fade right into the wall. So I’m a Rust-O guy cause that’s what we used in New York. Krylon just wasn’t effective unless if you were going to some primed or nice place or on trains — things like that. Rust-O opens up your ability to paint on so many different surfaces. I think at the time, kids were like, “How is he doing that? How is his stuff so solid?” Rust-Oleum just wasn’t there and you had to get a certain cap for the Rust-O that wouldn’t work on the Krylon. It was all a difference in technology and knowledge. That’s what made me stand out.

It’s surprising that there wasn’t anyone else writing graf there from New York.

No, there wasn’t. People maybe visited. Now it’s so globalized. Now there’s this style that runs that Tokyo, New York, SF way. At the time, zines and videos were starting to come out for subcultures like graffiti. There was starting to be more access. Today there’s a glut of books on graffiti. It’s super overdone.

So you stood out because of the paint you were using?

Yeah and the vision. A lot of kids in SF would go to the parking lot where all of the other graffiti was. Whereas I’d go everywhere else. I was killing the streets. The Mission school graffiti thing (Barry McGee, Margaret Kilgallen, etc.) was starting around that time. Barry was already doing kind of weird characters as opposed to letters. People did it in New York, but in that small city, he was the only guy doing it. He’s a big influence to a lot of people — the biggest for a very long time. And we would go out and paint and have fun.

Why’d you go back to New York?

A bunch of reasons. A part of it was that it’d just run its course. Moving back for me was really different because I’m not from the city and when I was a kid, I didn’t really go down to the Lower East Side. Avenue A was kind of the cutoff. There really wasn’t much down there at the time. It was a fucked-up place. And I didn’t know more than a few people.

What made you choose LES?

Everyone I knew moved to Williamsburg and I was distancing myself from certain aspects of the scene. I was more open to being around new things and what I’d already experienced in Cali was in Williamsburg. It was annoying.

What was your spot like?

My block where I lived, I didn’t know it at the time, but it had mad rats. It was really unpleasant. Getting home late at night, especially if you’re with a girl or something, it’s like, “Okay, I’m going to prepare you. Move slow. Don’t make any sudden movements. There are a lot of rats here.” There were so many that I’ve stepped on them. One time I kicked one, just in my stride. It was also a known dump block. Like if you wanted to dump a fridge or something, you’d dump it on my block. It was being gentrified. There were all these new businesses and that’s how I met Alife. They were just opening the store and Steve Powers (ESPO) was friends with one of the owners, Rob Cristofaro. He told me to go over there because they were having writers sign canvases and stuff as a decorative element for the shop. They were very open and inviting to anyone who was creative like, “Let’s talk and see what we can build.”

So what was the vibe of the space?

At the time, when they’d opened, it was kind of a consignment shop. They had shoes — but not like limited-edition sneakers. The sneaker thing hadn’t hit yet. They had jewelry and trinkets, t-shirts. We had just gotten dial-up Internet. You know, everyone had their hotmail account.

A whole world away.

Yeah. But you forget. It’s very important to remember the way that people communicated and shared information. I had been in San Francisco for like six years and I had studied, really, like Californian things simply by being there. When I got back to New York people didn’t know about the things I knew about. Also New York is super, super, super commercial. Like, “I’m a photographer. No, I’m not an art photographer. I’m shooting some editorial for some magazine.” They’re a dime a dozen here. So Alife was really a commercial exposure for me. It was really new and quite different and they saw me as different. I had a fine-art background. They came from design and fashion. They were open to just talking to people and building creatively. I lived around the corner and we ended up becoming really good friends.

The Alife guys encouraged you to first package your markers?

Yeah and I was like, why would anybody want to buy this? I was stealing all of my supplies. In the US, big business didn’t want anything to do with graffiti. They were like, “You kids are from the ghetto, crack-smoking minorities.” Whereas in Europe people saw it as a market because it wasn’t criminalized like it was here. They weren’t afraid of being vilified if they produced products for it. So in Europe it was developing pretty rapidly and some of that was beginning to come over to New York. New York is always influenced by Europe because of the proximity. California, on the other hand, doesn’t owe much to Europe. And then at the same time — this was ’99 or ’98 — Steve Powers came out with the first book published in America on graffiti since the ’80s called “The Art of Getting Over.” And I was one of like ten featured artists. I had a page where he wrote about me and Krink and there were a bunch of pictures. This was big press for me. And since I’d just moved back, a lot of people in New York hadn’t experienced my graffiti yet.

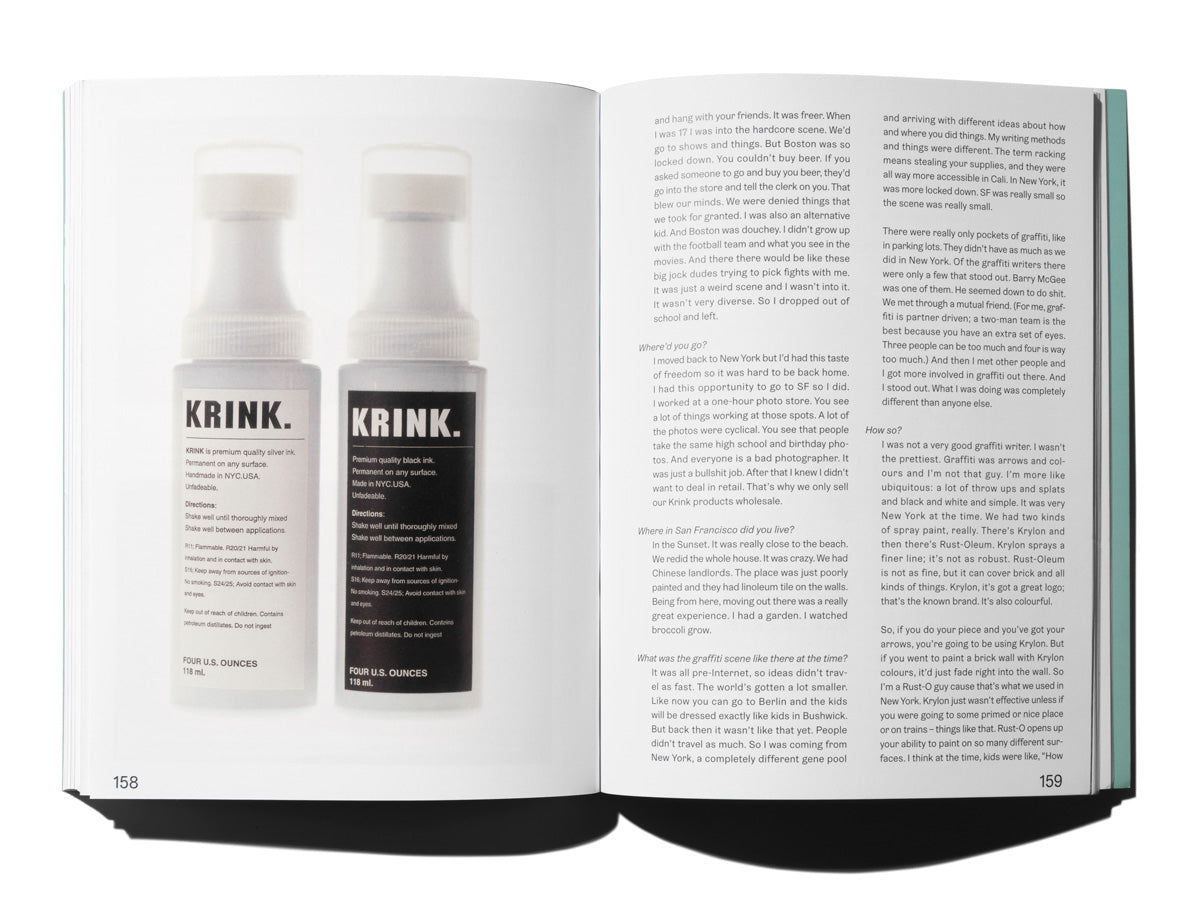

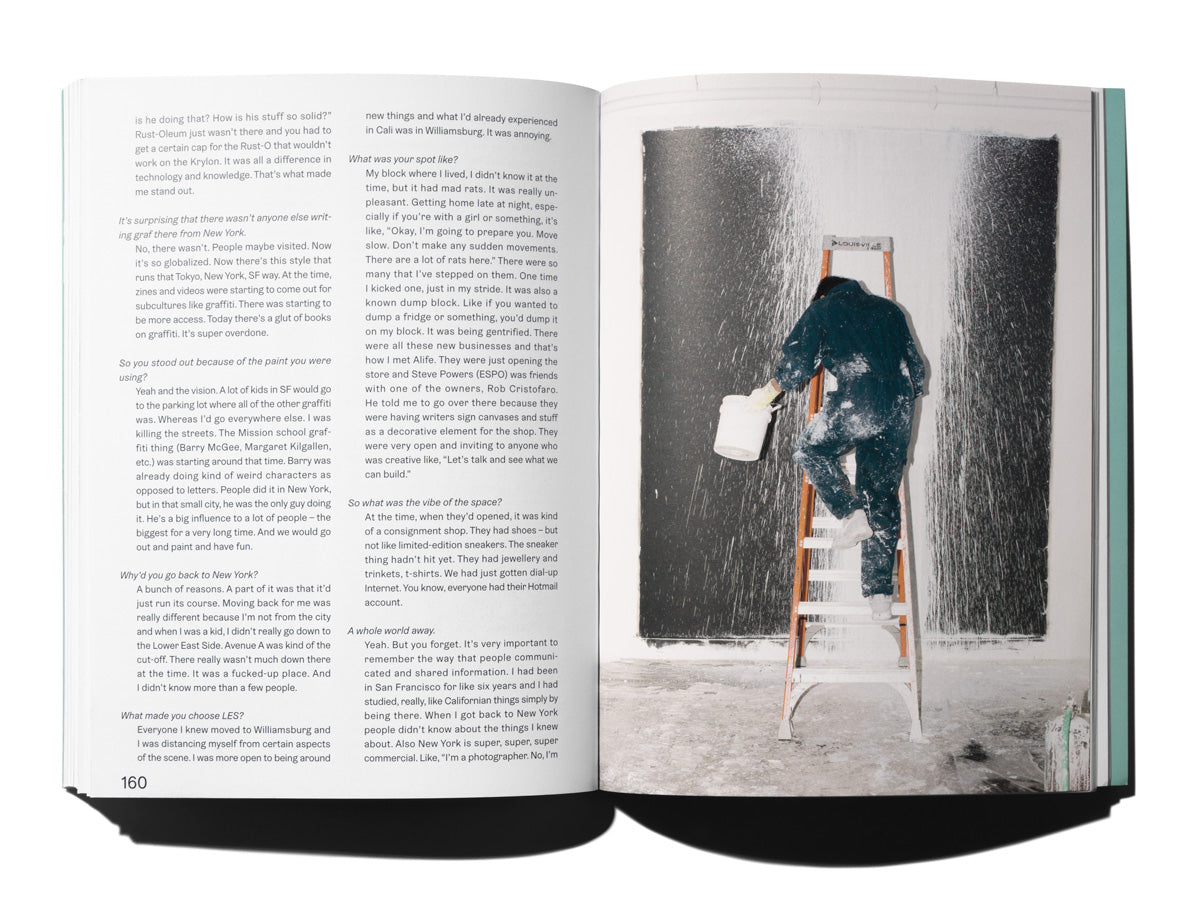

How’d you go about putting together the marker?

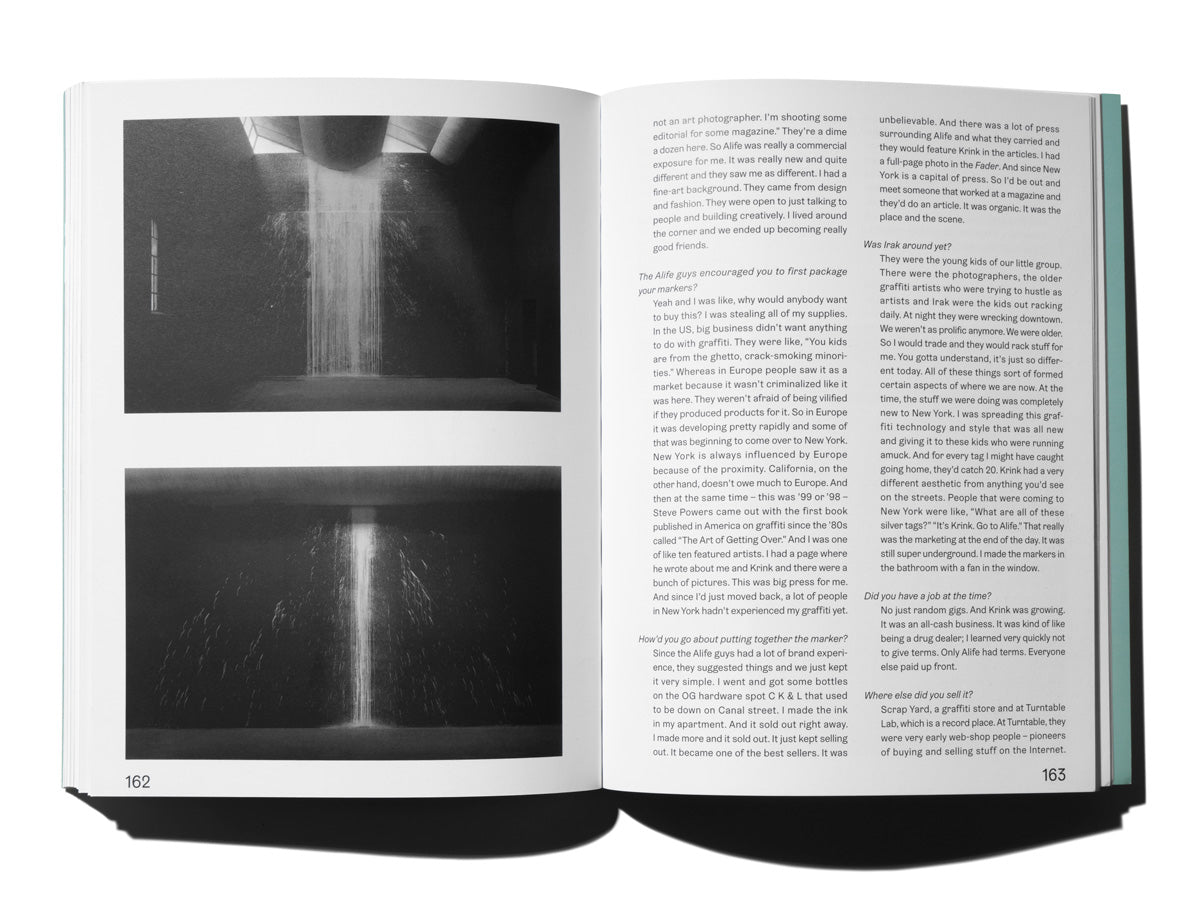

Since the Alife guys had a lot of brand experience, they suggested things and we just kept it very simple. I went and got some bottles on the OG hardware spot C K & L that used to be down on Canal street. I made the ink in my apartment. And it sold out right away. I made more and it sold out. It just kept selling out. It became one of the best sellers. It was unbelievable. And there was a lot of press surrounding Alife and what they carried and they would feature Krink in the articles. I had a full-page photo in the Fader. And since New York is a capital of press. So I’d be out and meet someone that worked at a magazine and they’d do an article. It was organic. It was the place and the scene.

Was Irak around yet?

They were the young kids of our little group. There were the photographers, the older graffiti artists who were trying to hustle as artists and Irak were the kids out racking daily. At night they were wrecking downtown. We weren’t as prolific anymore. We were older. So I would trade and they would rack stuff for me. You gotta understand, it’s just so different today. All of these things sort of formed certain aspects of where we are now. At the time, the stuff we were doing was completely new to New York. I was spreading this graffiti technology and style that was all new and giving it to these kids who were running amuck. And for every tag I might have caught going home, they’d catch 20. Krink had a very different aesthetic from anything you’d see on the streets. People that were coming to New York were like, “What are all of these silver tags?” “It’s Krink. Go to Alife.” That really was the marketing at the end of the day. It was still super underground. I made the markers in the bathroom with a fan in the window.

Did you have a job at the time?

No just random gigs. And Krink was growing. It was an all-cash business. It was kind of like being a drug dealer; I learned very quickly not to give terms. Only Alife had terms. Everyone else paid up front.

Where else did you sell it?

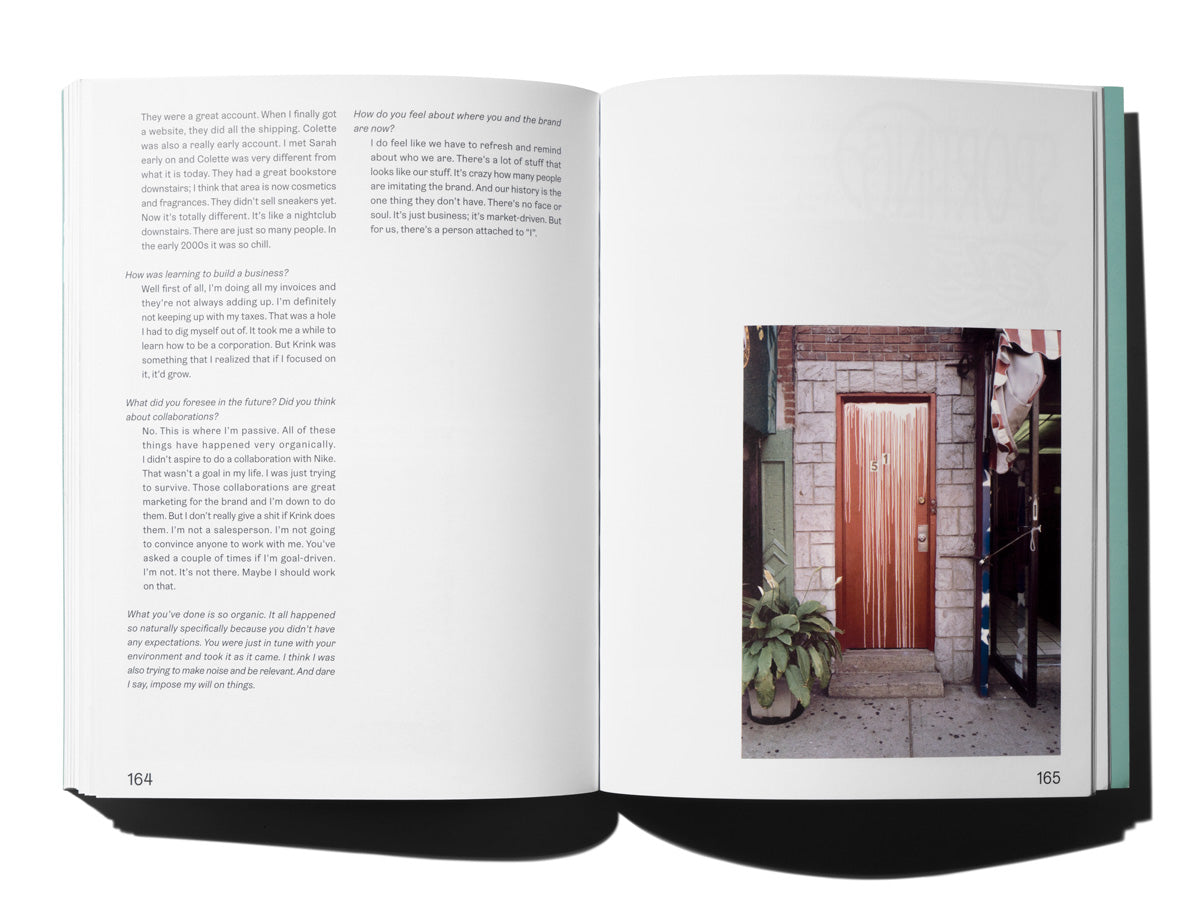

Scrap Yard, a graffiti store and at Turntable Lab, which is a record place. At Turntable, they were very early web-shop people — pioneers of buying and selling stuff on the Internet. They were a great account. When I finally got a website, they did all the shipping. Colette was also a really early account. I met Sarah early on and Colette was very different from what it is today. They had a great bookstore downstairs; I think that area is now cosmetics and fragrances. They didn’t sell sneakers yet. Now it’s totally different. It’s like a nightclub downstairs. There are just so many people. In the early 2000s it was so chill.

How was learning to build a business?

Well first of all, I’m doing all my invoices and they’re not always adding up. I’m definitely not keeping up with my taxes. That was a hole I had to dig myself out of. It took me a while to learn how to be a corporation. But Krink was something that I realized that if I focused on it, it’d grow.

What did you foresee in the future? Did you think about collaborations?

No. This is where I’m passive. All of these things have happened very organically. I didn’t aspire to do a collaboration with Nike. That wasn’t a goal in my life. I was just trying to survive. Those collaborations are great marketing for the brand and I’m down to do them. But I don’t really give a shit if Krink does them. I’m not a salesperson. I’m not going to convince anyone to work with me. You’ve asked a couple of times if I’m goal-driven. I’m not. It’s not there. Maybe I should work on that.

What you’ve done is so organic. It all happened so naturally specifically because you didn’t have any expectations. You were just in tune with your environment and took it as it came.

I think I was also trying to make noise and be relevant. And dare I say, impose my will on things.

How do you feel about where you and the brand are now?

I do feel like we have to refresh and remind about who we are. There’s a lot of stuff that looks like our stuff. It’s crazy how many people are imitating the brand. And our history is the one thing they don’t have. There’s no face or soul. It’s just business; it’s market-driven. But for us, there’s a person attached to it.