By Craig Costello

I grew up in Queens, NY in the ‘80s, where graffiti was already a part of the landscape and a symbol of New York City. I skated and listened to punk, hardcore, hip hop, and new wave. Most of my friends were creatives, skaters, and musicians. A lot of them wrote or dabbled in graffiti for fun; it was part of being young in NYC.

I was always interested in making things. I started making my own markers and ink by tinkering and experimenting with existing products. It was for fun and out of necessity. Most importantly, making my own supplies allowed me to create and control my aesthetics, which led to developing a style that was my own and stood out.

The street is a very harsh environment, sun, elements, dirt, grime. I needed an ink that wouldn’t fade and a marker tip that wouldn’t clog with dirt. I learned some paint works better on raw concrete and others have vibrant color, but need a primed wall. It was all a process, but I could keep trying over and over since shoplifting, or “racking,” was the norm. I was always on the lookout for materials. Checking janitor closets for caps and warehouse areas or office supply shops. There was little reference for graffiti beyond experience and a lot of trial and error.

In the early ‘90s I left NYC and went to San Francisco, CA, for no reason other than to leave. It was there the early Krink K-71 Ink Marker was created. I would modify UNI PX70s, a popular paint marker. I unscrewed them, poured out the paint and the mixing ball, which often made a clicking noise when you walked, and refilled them with my own homemade silver paint or a high quality black ink. Then, I would carefully mush and massage the marker tip. Just enough so the tip opened up a little and became softer, fatter, and more brush-like. There was no marker like it and it worked beautifully. It was my standard, everyday carry.

The Krink Mop also had early beginnings during this time as I was experimenting with shoe polish markers. I used to rack a bunch of shoe polish and clean them out, you’d usually see a bunch of them in my kitchen drying next to the dishes. Not all inks and paints worked in them (a lot ate away the foam tip), so I made a silver paint that could flow through and not break down the foam. I adjusted the viscosity and made the paint drippy, a little at first, then a lot. I worked in small batches so I could go out and field test the marker, take mental notes, and make changes to the next batch. I liked it drippy because it had style and there was nothing else like it. The paint was shiny and bright and the tags were as large as spray paint tags. I liked to make a tag that was almost illegible but held its form; it was part of my style. Anyone who wrote graffiti knew it was me.

The Krink Mop also had early beginnings during this time as I was experimenting with shoe polish markers. I used to rack a bunch of shoe polish and clean them out, you’d usually see a bunch of them in my kitchen drying next to the dishes. Not all inks and paints worked in them (a lot ate away the foam tip), so I made a silver paint that could flow through and not break down the foam. I adjusted the viscosity and made the paint drippy, a little at first, then a lot. I worked in small batches so I could go out and field test the marker, take mental notes, and make changes to the next batch. I liked it drippy because it had style and there was nothing else like it. The paint was shiny and bright and the tags were as large as spray paint tags. I liked to make a tag that was almost illegible but held its form; it was part of my style. Anyone who wrote graffiti knew it was me.

This was the invention of Krink, something new and unique. It was a technology that gave an edge in recognizability. It was fun, effective, and easy.

This was the invention of Krink, something new and unique. It was a technology that gave an edge in recognizability. It was fun, effective, and easy.

In 1998, I moved back to NYC into the Lower East Side. I met a group of designers, soon to be friends, starting a shop called Alife. They were open and inviting, and pushed me to sell my markers as a brand called Krink, based on KR’s ink.

I made the first Krink Silver mops and 8oz bottles in my apartment. It was just me, mixing ink, hand-filling bottles, printing out labels, and gluing them onto the bottles. It was a bit crazy and I had to figure it out as I went. I used to go to a hardware shop on Canal Street to buy bottles for the ink, eventually they were placing special orders for me. I took cabs with cases of bottles in the trunk and back seat.

I made the first Krink Silver mops and 8oz bottles in my apartment. It was just me, mixing ink, hand-filling bottles, printing out labels, and gluing them onto the bottles. It was a bit crazy and I had to figure it out as I went. I used to go to a hardware shop on Canal Street to buy bottles for the ink, eventually they were placing special orders for me. I took cabs with cases of bottles in the trunk and back seat.

Alife sold Krink in the shop and it sold out immediately. I made more, and it sold out again. I was outgrowing my setup, and eventually got a studio share to move the whole operation out of my apartment. Alife and the LES was a place for young people and creative inspiration; people who came to visit NYC would see Krink in Alife and the LES covered everywhere with drippy silver tags. It helped bring exposure to Krink.

Alife sold Krink in the shop and it sold out immediately. I made more, and it sold out again. I was outgrowing my setup, and eventually got a studio share to move the whole operation out of my apartment. Alife and the LES was a place for young people and creative inspiration; people who came to visit NYC would see Krink in Alife and the LES covered everywhere with drippy silver tags. It helped bring exposure to Krink.

The demand for Krink continued to grow. I found a USA-based factory that, by today’s verbiage, would be called artisanal. Krink is still made in this factory today. We collaborate to create formulas and markers in small batches, which is a significant advantage to maintaining quality and developing new products. I began hiring staff and building a network of suppliers and it brought more growth to the brand. It was a tremendous change, knowing that I could step back from production and focus more on development and design projects.

The demand for Krink continued to grow. I found a USA-based factory that, by today’s verbiage, would be called artisanal. Krink is still made in this factory today. We collaborate to create formulas and markers in small batches, which is a significant advantage to maintaining quality and developing new products. I began hiring staff and building a network of suppliers and it brought more growth to the brand. It was a tremendous change, knowing that I could step back from production and focus more on development and design projects.

In the street, I was transitioning from writing my name to creating abstracted works with Krink drips on mailboxes, doors, and more. I used the same materials and continued to invent and repurpose tools, but the outcome was completely different. Soon, I wanted to scale up. I started painting with fire extinguishers that I filled with paint. They are messy, difficult to control, chaotic, and unpredictable. I used to practice in the abandoned stairwells of my old studio building, modifying the paint mixture and pressure as I went. Now large buildings were in play and I could paint the side of a building creating site-specific installations.

In the street, I was transitioning from writing my name to creating abstracted works with Krink drips on mailboxes, doors, and more. I used the same materials and continued to invent and repurpose tools, but the outcome was completely different. Soon, I wanted to scale up. I started painting with fire extinguishers that I filled with paint. They are messy, difficult to control, chaotic, and unpredictable. I used to practice in the abandoned stairwells of my old studio building, modifying the paint mixture and pressure as I went. Now large buildings were in play and I could paint the side of a building creating site-specific installations.

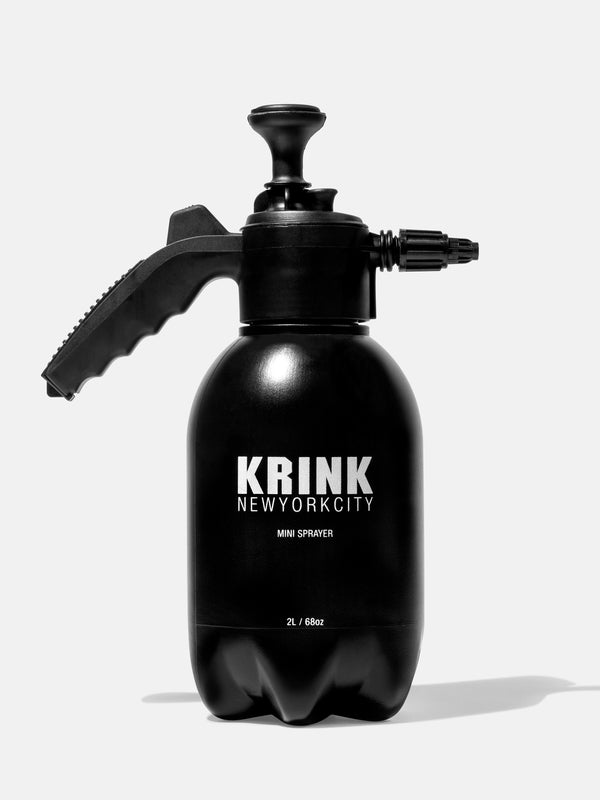

After using the Krink Extinguisher for some time, I wanted to scale down a bit for working on smaller walls, interior walls, and canvas. I used sprayers, tools commonly used for gardening and insecticides. Sprayers are pressurized by hand, not like extinguishers which are pressurized by a compressor, so I began experimenting again with paint mixture, viscosity, and pressure to find a balance that worked and I liked.

After using the Krink Extinguisher for some time, I wanted to scale down a bit for working on smaller walls, interior walls, and canvas. I used sprayers, tools commonly used for gardening and insecticides. Sprayers are pressurized by hand, not like extinguishers which are pressurized by a compressor, so I began experimenting again with paint mixture, viscosity, and pressure to find a balance that worked and I liked.

It was only fitting to develop these unique artist tools for Krink. I wanted the brand to continue to grow into new areas and share more inventive methods of mark-making.

As I began painting more abstract works, it attracted a new growing audience, which brought new opportunities. I was receiving invitations to paint site-specific installations and participate in exhibitions all over the world.

As I began painting more abstract works, it attracted a new growing audience, which brought new opportunities. I was receiving invitations to paint site-specific installations and participate in exhibitions all over the world.

Simultaneously, Krink was expanding with new products and creative projects. Though I had no formal design experience, my background in art and photography drove the aesthetics of the brand. I liked simplicity and wanted to steer away from what I saw as trendy. Krink is neutral, industrial, clean, and ambiguous. I want the products to look nice and be attractive as an object, but maintain a high level of functionality.

Interested in the aesthetics of my work and Krink, brands began reaching out for collaborations and special projects. Krink quickly became an established creative studio partnering with artists, designers, and brands from around the world.